Last week Adrian Chen conducted an e-mail interview with me about @everyword. Here’s the resulting article on Gawker. The @everyword account gained about a thousand new followers as a result of the article—not bad for an account that just tweets word after word every half hour!

It’s been interesting to read people’s reactions to @everyword (and yes, I have the Twitter search for @everyword in my RSS feed reader, because I am hopelessly narcissistic). For the most part, the reactions are positive! It’s satisfying when someone is amused by a word that they didn’t know existed (or that they hadn’t considered to be a “word”) or when someone finds unexpected synergy between a word that just got posted and something that is happening in their lives.

Some of the reactions are more critical. Here’s one reaction in particular that I wanted to respond to, from Twitter user @fran_b__:

@everyword They aren’t words unless they have meaning, which implies context. Stripped of context, they are simply (python) string arguments. (source)

This response baffled me, because in my mind @everyword is all about context. For example, here’s the way that I typically read @everyword:

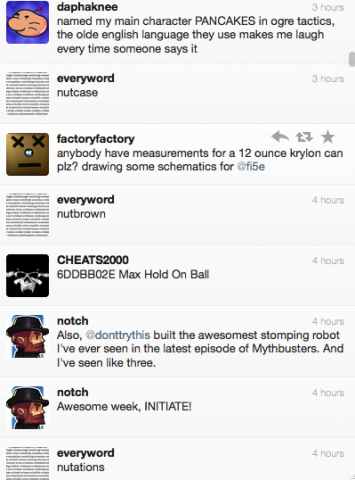

This is a screenshot of my Twitter client on a typical morning. You can see the tweets from @everyword interleaved in the feed. I don’t generally read the tweets in my feed like I would paragraphs or sentences in an essay or a piece of fiction (e.g., I skip tweets, I don’t necessarily expect cohesion from one tweet to the next), but I do tend to read them in sequence. It’s undeniable that the tweets exist in the same physical context here. Because of this, some interesting possibilities for creative reading crop up. It’s easy for one tweet to “color” how nearby tweets are read, for example. I’m not saying that @notch is prone to nutations, or that @factoryfactory and @daphaknee are nutcases, but that’s certainly a reading made possible by the tweets’ close proximity.

This is a screenshot of my Twitter client on a typical morning. You can see the tweets from @everyword interleaved in the feed. I don’t generally read the tweets in my feed like I would paragraphs or sentences in an essay or a piece of fiction (e.g., I skip tweets, I don’t necessarily expect cohesion from one tweet to the next), but I do tend to read them in sequence. It’s undeniable that the tweets exist in the same physical context here. Because of this, some interesting possibilities for creative reading crop up. It’s easy for one tweet to “color” how nearby tweets are read, for example. I’m not saying that @notch is prone to nutations, or that @factoryfactory and @daphaknee are nutcases, but that’s certainly a reading made possible by the tweets’ close proximity.

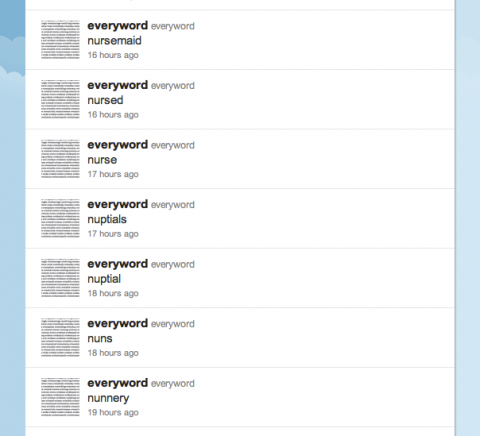

There’s also the context provided merely by being in sequence with other words in the @everyword feed. Here’s an example:

I find this endlessly fascinating. When you see these words juxtaposed like this, you can’t help but try to find some connection between them. In some cases, the connection is grammatical (nunnery is of course morphologically related to the word nuns). But nuns, nuptials and nursemaid together like is almost like a little narrative. “Nuns can’t have nuptials, and they certainly can’t be nursemaids.” It seems ironic that the words would be juxtaposed like this, and that perception only emerges from seeing these words in this kind of unusual context.

It’s also a cultural practice of ours to consider individual words in the abstract: we pick out our favorite words, we decide which words are commonly misused, we decry our politicians for making up words or using words with a disagreeable frequency, etc. In some sense, a word carries with it a cultural context, no matter where it occurs. One of the intentions of @everyword was to play with this idea: every word has cultural baggage. What would happen if we systematically exposed ourselves to that baggage?

Even if I concede that the words in @everyword are “simply (python) string arguments,” isn’t that also a context? A computer program is a kind of writing, after all. It means something for a programmer to choose to put one string in a program, instead of some other string, or to feed some set of data to a program instead of some other set. Sure, the Python program that runs @everyword would also work with any other arbitrary data set—@everybaseballplayer, anyone?—but the fact that I chose words, and words in this particular order, is part of the context of the piece.

In the end, I think @fran_b__’s implication is that there are certain kinds of contexts that a word can occur in that “count” as meaningful (such as being in a sentence intentionally composed by an individual) and others that don’t. I suppose that for certain fields of study, this is a valid point of view: if you’re analyzing a novel, for example, you might not want to include in your analysis the novel sitting next to it on the shelf. As a writer and poet, however, I find that limitation pretty dull. There’s never been an era in history with such diverse practices for reading and writing text. Why not have as much fun with that as possible?